Why Do People Keep Writing Books?

This is part 3 of my observations about the book business, an industry I’ve been intimately involved in since 1989 as a bestselling author, professional ghostwriter, self-publisher, small imprint owner, and educator. You can read Part 1 at https://bit.ly/4dlbI29 and Part 2 at https://bit.ly/3QD2JQc. Further writings will (eventually) be available in This Business of Books: A Complete Overview of the Industry from Concept through Sales, 6th edition, in progress.

I first listed the reasons people write books in the original version of This Business of Books: A Complete Overview of the Industry from Concept through Sales back in 1991.

To communicate

To chronicle their times

To preserve their heritage

To share a story or advance an idea or prove a point

To touch other human beings

To have an impact on society

To leave their mark in the world

To make some money

It wasn’t entirely my enumeration. I was relatively new to the book business at that time, having just come off a quasi-competent career as a club musician and blustered my way into bestselling authorship without half a clue as to what I was doing. But a friend with multiple sclerosis introduced me to a guy on the other side of the country from whom she got a supplement that would theoretically help with my multiple sclerosis, so of course I began ghosting late-night infomercial titles for him.

That’s a long story of which I’m alternately proud and ashamed, so suffice to say the list above is partly scarfed from various other writers and partly my own experience and observation. Despite Samuel Johnson’s contention that, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money,” millions of men and women do.

Most, in fact.

I won’t try to math this out, but reasoning works just as well. Amazon’s backlist includes some 32.8 million titles, only a slim sliver of which will recoup as much as their copy-editing cost. Add to that the untold millions of books that are purposely not published—far, far more than you may think.

Some are too secret, too personal. When my aunt wrote her autobiography, I expect she revealed childhood and family secrets that would have provided some closure for her sister, my mother. But once she’d cathartized her soul, she burnt the manuscript rather than share. For many people, life is pain.

A famous, award-winning athlete refused to let his ball club publish the final draft he and I put together after many, many rewrites. The club had tens of thousands of readers waiting, but he’d been too honest; he couldn’t bear revealing his truth to his fans. He paid tens of thousands of dollars to make sure his book said what he wanted to say, the way he wanted to say it, because he had to. He needed to purge his soul. And then he printed it out nicely, put it in a folder, and made it go away.

My very first undercover author refused to release his fascinating title to the public, despite getting permission from Langley to publish. His historical truths about how OSS segued into the CIA and how agents with no flight experience or even interest were trained and licensed to fly multiple aircraft in fifteen days are now lost to all but 250 select friends and family.

The “one-percenter” CEO whose book woulda been a “duh” slam-dunk bestseller, went to his grave without his ethics-laden memoir reaching anyone because his family got the rights to the work in his will… including the right to nix publication.

A delightfully articulate author chose to put her charming exposé about a seldom-addressed segment of society in a drawer. Turned out she’d never intended to get it published; she just wanted to preserve her stories for her family.

And that’s the point, isn’t it? Since the non-recorded beginning of time, we humans have been telling each other our stories. Passing along information. Educating, conversing, touching, proving, preserving, provoking discussion, debate, and yeah, disruption, with our words. We write because we need to share.

Because life, at its most fundamental, is about love, community, and helping others. The rest is just distraction. Love, community, and helping others. Merely every single religion and philosophy preaches the same concepts.

I make my living writing books for people with great ideas, but I write my own books because, like everyone else, I have ideas and facts to share, stories to pass on, information to disseminate, and love to send out to my community. It doesn’t matter that said community fits inside a walnut shell. It’s the intention that matters, the doing of the thing.

That’s why people keep writing books, and why people keep trying to erase, minimize, and discourage other people’s book writings. Consider that slaves didn’t just build the United States; they built everything. Slavery has existed since before recorded history. And humans have changed little in the interim. So where are the books, the writings, about that reality? Likely long destroyed. To the victors go the spoils—and the historical dominance.

And yes, writing a book is a tremendous undertaking. Yet once started—hell, once imagined—the work takes on a life of its own and until it’s written, it will elbow your mind, nudging, pushing, “Hey, don’t forget me! I’m still here, waiting to be written!” Not an endeavor to be taken lightly.

All of which naturally leads to the most important question I ask authors: how will you define success for your title?

I don’t know why this isn’t more obvious, but even for “pantsers,” i.e., authors who write by the seat-of-the-pants rather than work off an outline, the why behind a book is crucial. Granted, sometimes we don’t know it when we initially put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard, but once we’ve finished that first draft, we understand what we’re doing. We can parse out the critical thinking aspect of the work: its core thesis or theme, the emotion we’ve brought to the work and the emotion we hope/intend/expect to rouse in a cold reader.

I’m using the industry definition of “first draft”—which means the work is fully written to the author’s satisfaction but not yet elevated to meet traditional publishing standards or satisfy reader expectations—not the typical writer’s definition, which means they’ve finished writing everything down.

We know what pushed us to pen the work. We know what we’re pushing back against and why the work is important… to those who will find it so. The perfect time for a little self-honesty, to wit: what is our number one objective? Sure, sure, we want a bestseller sticker… we may even aspire to traditional bestselling status.

Realizing, of course, that Amazon, New York Times, and all other bestselling lists can be and are frequently gamed. But let’s don’t go there right now!

But… is that all? Or are we hoping to get rich from our single volume? Spoiler alert: that ain’t agonna happen.

Do we want thousands of people to read our words, thoughts, advice, the tale we’ve carried in the back of our head for years? That’s entirely possible—if we a) have a realistic, long-term plan to get the book in front of said folk, b) implement said plan with gusto, and c) continue to work the plan, modifying and upgrading as life, society, and tech dictate.

Is our purpose really to join the social discourse of a specific topic, to put our thumbprint on a hot-topic or evergreen discussion, to leave our mark, to put our ideas, wordings, and spins “out there” for all the media and pundits to quote?

Are we aiming for the status and outreach that cometh with being an author, with adding our title to our e-signature, using the book to boost our reputation, increase our influence, open doors and support our business / social / religious / political / philanthropic endeavors?

Could it be we must needs let our progeny know who we were, what we did, how we accomplished, where we failed, remember this, try to avoid that, above all else I love you…

Or do we simply need the catharsis, the release, the personal satisfaction of getting it out of our head, our guts, our essence, so we can move on to life’s next challenge?

Which one makes us get up every morning thinking, “I’ve got to write that book!” Which one will give us solace when we settle down at night, thinking, “I did it. I’m proud of me.”

Which one will makes us feel that all our time, money, angst, and fear was worth it?

That’s a lot to chew on, isn’t it? Allow me to simplify… and expound a bit.

If’n your principle goal is a bestseller sticker, to pursue the impossible dream of making it rich with a single title, or for thousands of strangers to read your work, you’re writing what we ghostwriters call a public book. Almost all first-time books by first-time authors fall into that category.

A “public” title is sold or given away as individual units or in small orders primarily to gain readership and to strive for bestseller status. You can deduct each unit’s cost against its profit upon sale. Most fiction, memoir, and nonfiction books are intentionally for the public; buyers are found through personal platforms, focused off- and online market placement, targeted online promotion, and live-audience interaction. ROI is calculated against distribution, marketing/promotion, and advertising outlay, not against production expenses (writing, editing, pre-press, printing), which are considered COGS, or Cost of Goods Sold.

Suppose on the other hand, you are a business person of some or any sort. And suppose the book you envision—your first, second, or twenty-fifth—speaks directly to potential constituents or is an integral component of or dynamic presentation for the system, program, or service you provide. That expands your public book into a purpose title. Purpose titles include manuals, workbooks, textbooks, and so on.

A nonfiction “purpose” title may be sold in individual units and positioned/placed as a public title, but its primary intent is to a) market or promote a brand or business or b) serve as an integral part of a revenue-generating program. Any business-oriented book can logically reap a higher ROI by positioning it as a commercial product or as both trade and commercial rather than as strictly trade. Some banks will underwrite titles if they are an integral element of a larger business plan.

Buyers are found through personal, online, and corporate/organization interaction; consequently, COGS are deductible in full at the time of the expense, even if you are not the publisher of record. Talk to your accountant for guidance about your tax liabilities.

Private, or legacy titles, are exactly what their name implies.

A ”private,” or legacy book is not intended to produce an ROI. Typically gifted rather than sold, its cost is nondeductible.

Since private books are, ya know, private, i.e., not marketable properties, you can put them together as you will. Stay 100 percent focused on getting your soul onto the page, saying what you want to say the way you want to say it. This is your book, meant to be shared only with people who already know and love you.

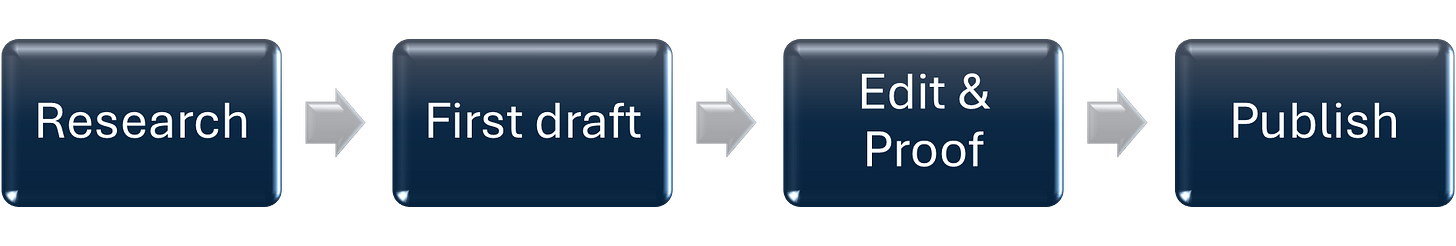

[Typical 4-step book creation process, most viable for private or legacy titles.]

I’d like to say that at most non-writing authors who aim for a public title know to work with an experienced writer or ghostwriter, someone who can maintain their voice and style while ensuring the work has both industry and cold-reader appeal… but we all know that’s not true. Even a cursory review of recent Amazon-published titles verifies that the typical creation sequence even for public titles comes down to:

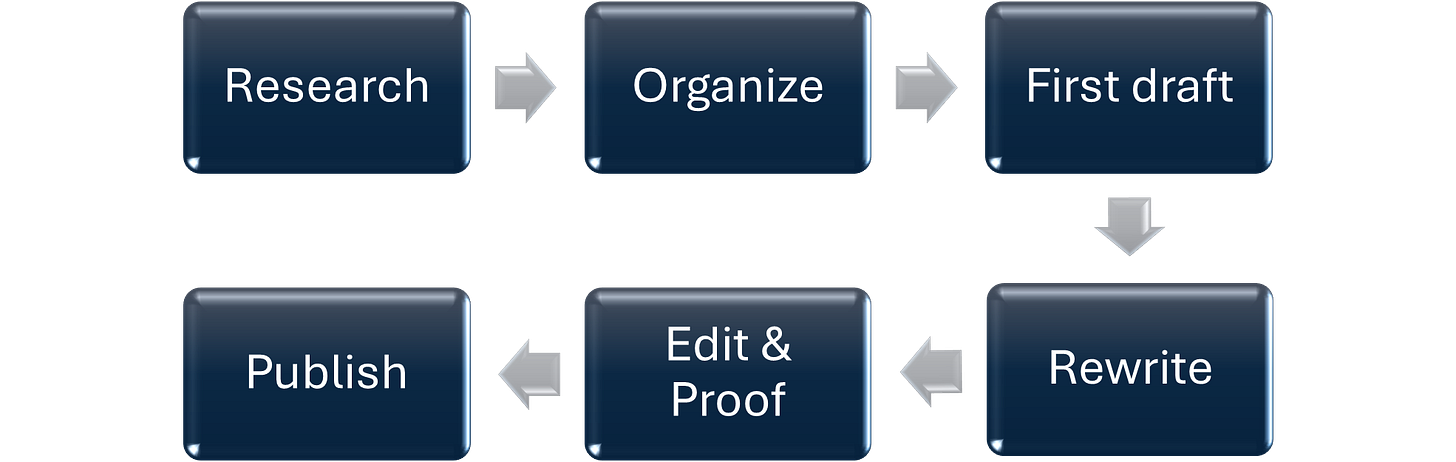

[Most common 6-step personally satisfying creation process, most viable for non-traditionally published titles.]

The upside here is that, again, the book says exactly what you want it to say, exactly the way you want it said. And if your primary goal is to chronicle your times; share a story, advance an idea, or prove a point; touch other human beings, or simply leave your mark in the world, this process works. It likely won’t help you have an impact on society or generate a significant ROI, but it is salable to friends, family, colleagues, and, most importantly, audiences. People you engage during personal appearances—live talks, presentations, and speeches—want to take a piece of you home with them, because they want more of you, exactly as they met you.

As the saying goes, however, what makes ya breaks ya, right? Books created using this extremely popular, nearly universally accepted, process are slush-pile fodder. There’s no way to count the number of truly fantabulous ideas consigned to near oblivion because the author opted to research, organize, write, rewrite, and edit their manuscript, and then submit it to agents and publishers before giving up and releasing it through Amazon. I mean, what else are they supposed to do?

Create a second draft—a truth that effectively takes us all the way back to the beginning of this series: Déjà vu all over again just like before.

Because the book business has always been thus. People with wonderful ideas have always trusted that writing/rewriting/editing their story, their memoir, their true crime, their health & fitness advice, yadda/blah/etc., until it was personally satisfying was the gateway to literary success.

They so seldom realize that personally satisfying is a literary trap. It (not always, but so often) indicates ego book, a title by, of, and for the author. “I want the reader to want what I want to share the way I want to share it.”

Those select manuscripts that make it through the traditional-publishing gauntlet are either legitimate second drafts… or are so strong, so fresh, so compelling they warrant a little protocol bending. And the author may well end up being offered an in-house subsidy deal.

I’m sorry; thought that wasn’t a thing anymore? Think again, me hearties.

A legitimate second draft adheres to traditional book-industry standards. It has editorial accountability. It meets gatekeeping-algorithm requirements. It’s formatted correctly, is Chicago Manual of Style compliant. It uses a standard nonfiction template, recognized memoir structure, or conventional fiction architecture.

If it’s a novel, it’s compelling and plausible within itself. As a memoir, its reflection is woven into the narrative. Nonfiction reveals, explains, demonstrates, and illustrates. And above all else, the book “reads.” It has Slinky® flow. It has energy, purpose, pacing, and resonance. It’s 100 percent written for the reader’s satisfaction, not the author’s.

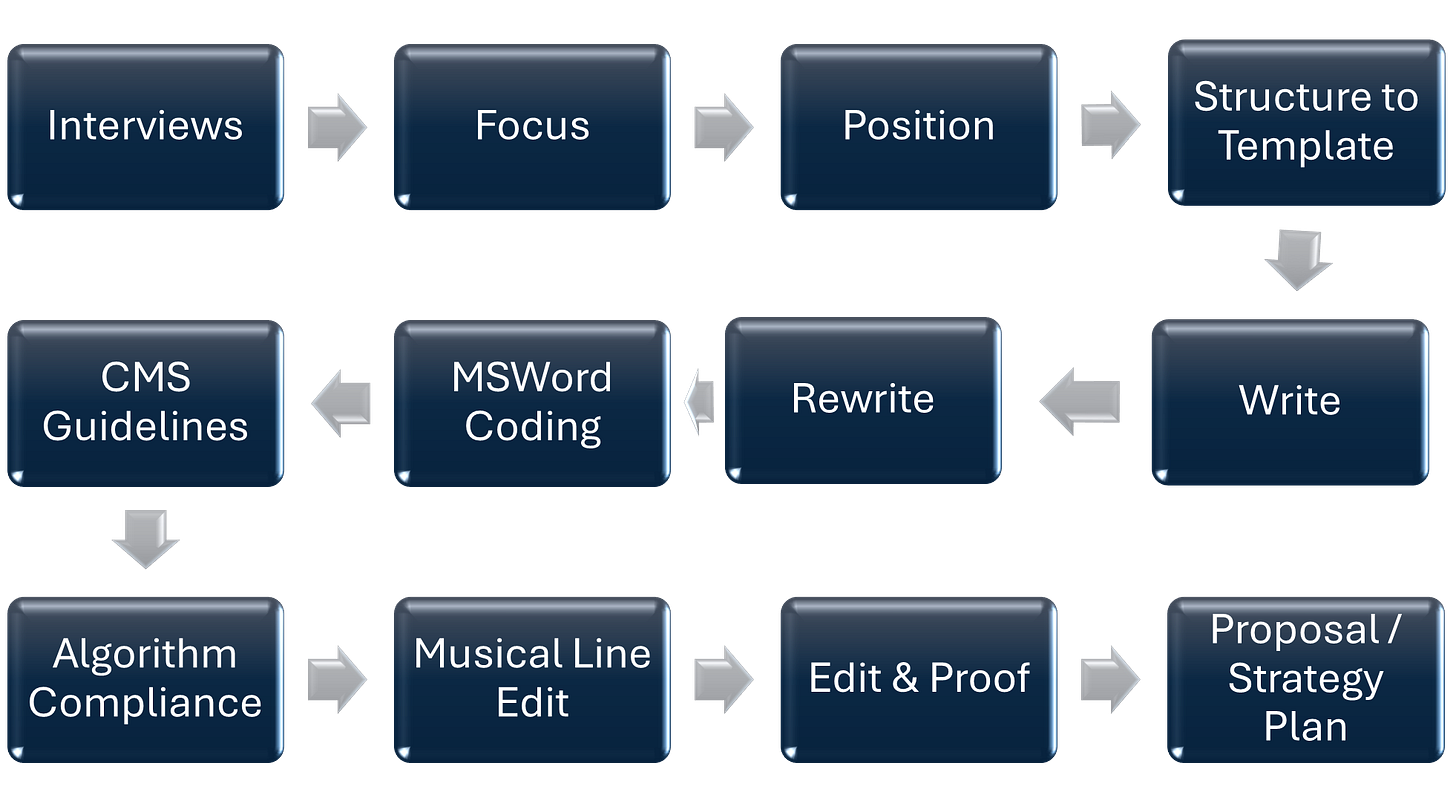

Ergo, it was likely created using this kind of process:

[Professional 12-step creation process, viable for traditionally published titles.]

Like with every other methodology, you get to say what you want to say, the way you want to say it—that’s what all first drafts are for, no matter how many times they’re rewritten or edited—but those ideas are specifically focused to fulfil your personal definition of success and positioned for its three best markets. Moreover the book is massaged to resonate with both cold readers and industry players before it goes for final editing and proofing.

The downside to this enhanced process is pretty obvious, of course: you get what you pay for. And still, there are still no guarantees you’ll land an agent or Big Five publisher—

… unless you’re a celebrity, are authoring in a high-profile title within its “headline” window or are a franchise novelist.

Ain’t that déjà vu all over again, just like before?